Roughly a quarter of workers in the United States quit their jobs in 2021. There has been a lot of talk about a supposed “labor shortage.” In theory, these conditions should be conducive to labor organizing—yet a real strike wave has not emerged. How have employment conditions changed, and what new strategies are likely to succeed in enabling people to stand up for themselves and each other against the capitalist economy? In a forthcoming series of articles, we will explore these questions.

This week, workers at Kellogg’s concluded a strike, accepting a new contract that their union declared to be a victory. A notorious anti-work Reddit page played a role in preventing the company from replacing the strikers, pointing the way to a symbiosis between workplace organizing and anti-work subversion. Here, we present a narrative about the working conditions that laborers face in another industry served by the same union.

Author’s Preface

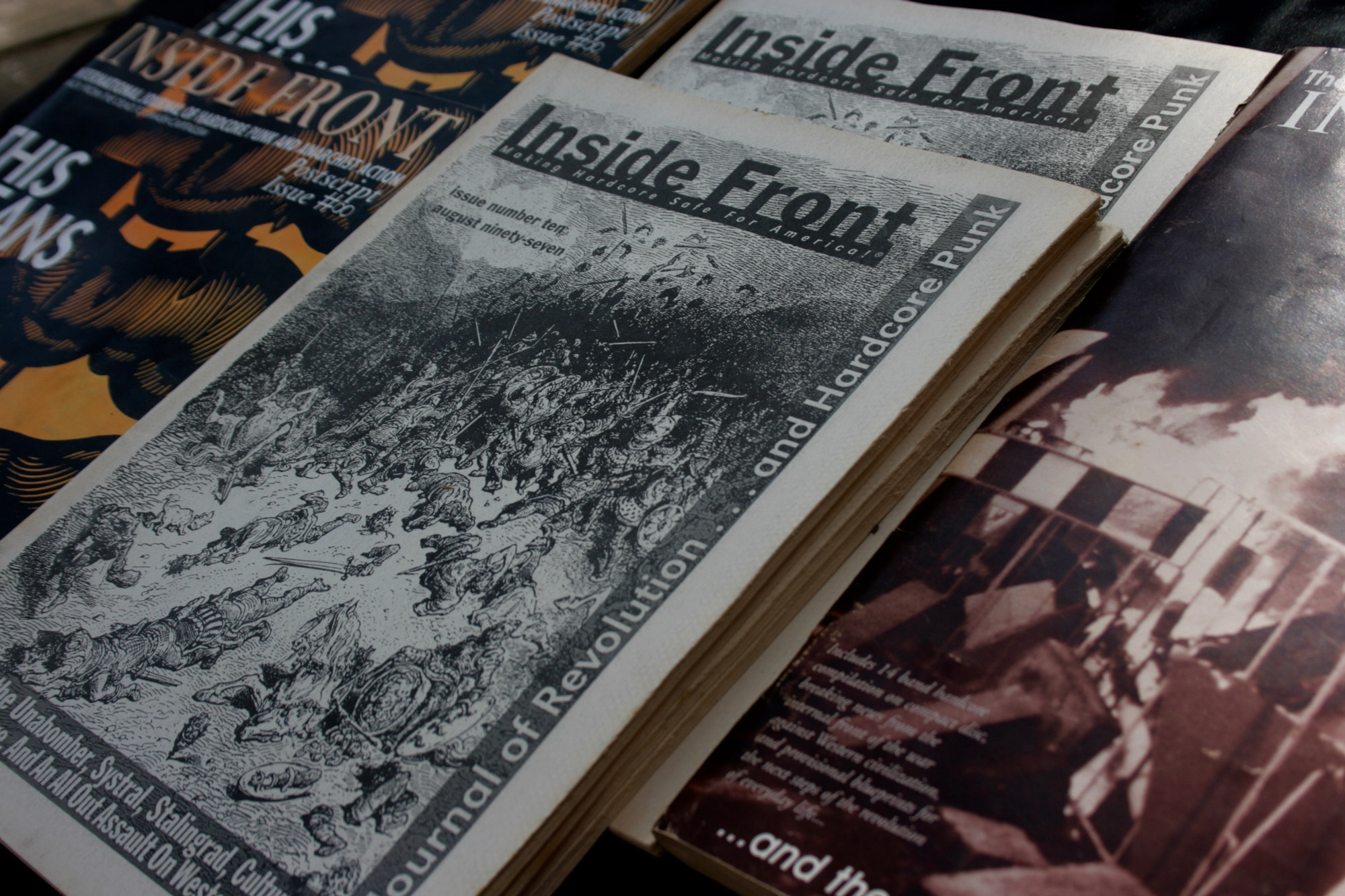

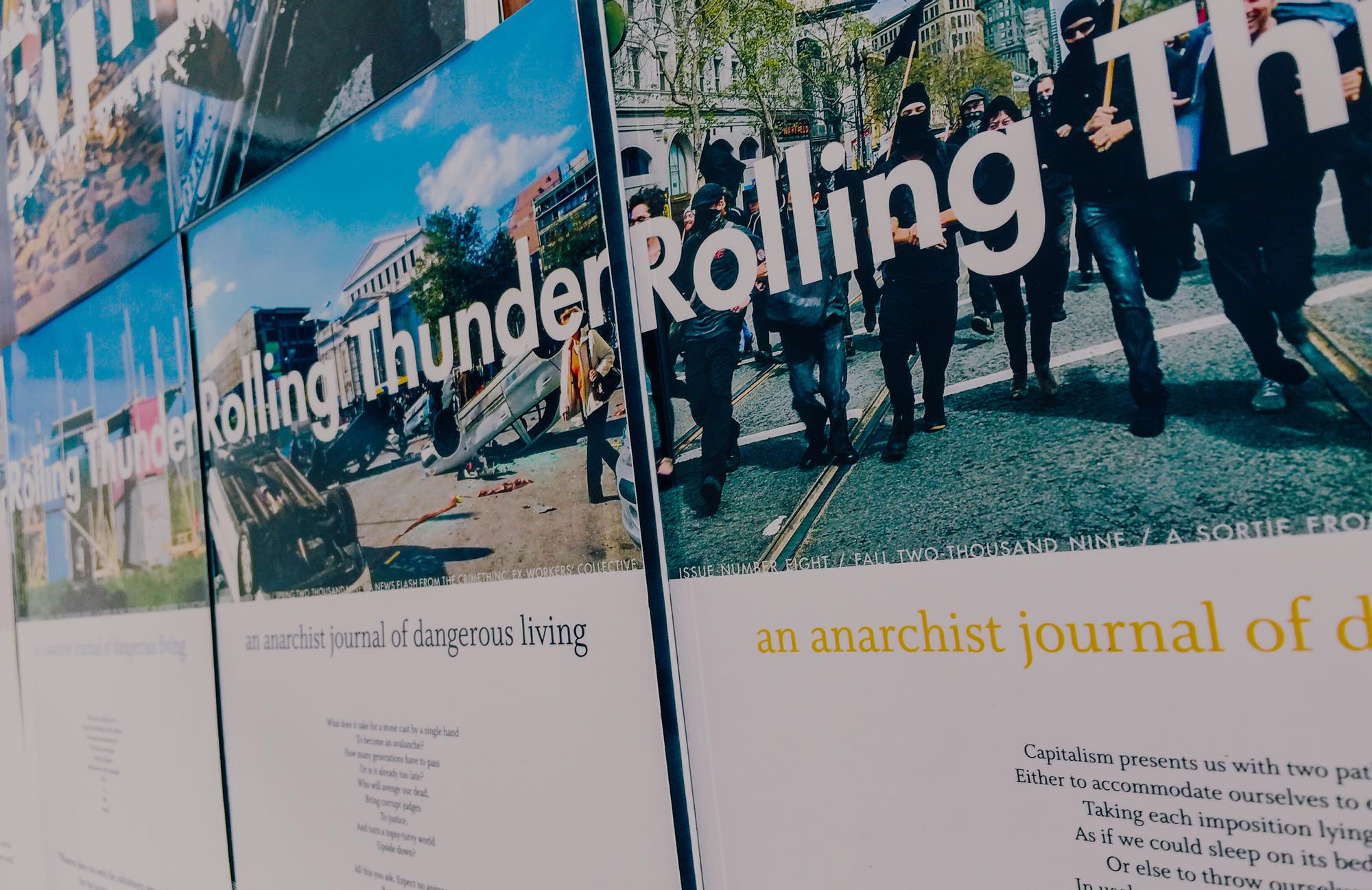

Congratulations to the Kellogg’s workers at the end of their 77 day strike! Their struggle is especially close to my heart, because I too was a member in good standing of the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers, and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM) for nearly ten years during the 2000s, during which time I worked seasonally at a beet sugar factory in Minnesota. As a small show of solidarity, I’d like to share an account that I wrote about the job back in 2005, which was printed in the first issue of Rolling Thunder.

Needless to say, much has changed since then—in the factory, the town, the union, and the world at large. My account is perhaps most interesting as a snapshot of industrial work at a particular time and place, and of a few of the frozen exploited maniacs who could be found laboring there at the point of production. What has not changed is that life under capitalism is nothing sweet, and that nothing is gained without struggle. Victory to the Kellogg’s workers!

Supporters of the striking Kellogg’s workers made these silent agitators to affix to grocery store shelf labels and cereal boxes. For use with Avery brand 8160 Address Labels or the equivalent. Click on the image to download a pdf for printing.

Where Sugar Comes from

So here’s the deal. Every fall I work in this beet sugar factory in western Minnesota. A whole lot of the sugar that goes into all kinds of processed food comes from sugar beets, and a whole lot of those sugar beets come from western Minnesota. The county where the factory is located is dead flat, except for the Minnesota River valley, and it contains precisely three things: corn, soybeans, and sugar beets as far as the eye can see. It’s completely rural, but at the same time, it’s every bit as unnatural as Los Angeles or Disneyland.

Every year in September, the beet farmers start pulling their crops. They pull them out of the ground with a combine, load them onto a semi truck, and drive them down to the plant. It takes the plant until spring to process the whole harvest, so they have to store the beets outside in seven gigantic piles, and they have to hire seasonal workers to run the machines that unload the trucks. By the end of the harvest season each one of the piles is bigger than a football field, and up to thirty feet tall. It’s one whole hell of a lot of beets.

It’s good money. The farmers pull beets all day and night, unless it’s too hot, or too cold, or too wet. Seasonal workers—beet pilers—work twelve hours a day, every day, as long as the farmers are pulling. This amounts to eighty-four hours a week if the weather cooperates, and the overtime adds up quick. Anything over eight hours a day or forty a week is time and a half, and Sunday is double time. If I live extremely frugally, I can make enough money there to fund my activities for the better part of the rest of the year.

The town is exactly like every other agricultural town of its size. There is a bar, a diner, a hardware store, two gas stations, a post office, a library, and a police station. The faces behind the counters almost never change from year to year. The tallest building is the grain silo, and the town ends abruptly where the beet fields begin at the edge of the last family’s yard. If you walk the railroad tracks two miles east you’ll get to the factory. The whole place is ordinary in every way, except that once a year it is crawling with beet pilers.

There are three kinds of people that pile beets: the Locals, the Latin@s, and the Kids. Western Minnesota was stolen from its original inhabitants in the nineteenth century, and has been populated almost exclusively by white people of Scandinavian heritage ever since. Recently, however, a lot of Hispanic folks have moved up there looking for work. There is a sizable Latino/Latina minority in both the town and the factory.

And then there are the kids. It’s a strange phenomenon, but every fall the town is overrun with wild looking young people from Somewhere Else with dogs and facial tattoos who work beets because the money’s good and they don’t ask many questions. I am one of them.

There really isn’t anywhere in town to accommodate all of us in any conventional sense, so almost every year we end up staying somewhere different. There used to be a fleabag motel down the road that would rent to beet pilers, but they got shut down for copious code violations. Last year about forty of us occupied an abandoned farm just past the outskirts of town. It was sort of like a band of vagabonds descending on a medieval village. I was a little bit worried that babies were going to start turning up missing and that the townspeople were going to come after us with pitchforks.

One year, the weather was terrible. Nobody was working or getting paid, and nearly everyone was camped out at the bar for days on end, getting ferociously drunk and terrorizing the town. Eventually the law got involved. But the hell-raising proved to be a surprisingly effective strategy. The next year the company tried really hard to work us no matter how bad the weather got, presumably just to keep us off the streets.

Another time, the bartender went down to the farm to hang out with us after work. She rolled up on a grim horde of beet pilers, solemnly skinning and eating a puppy around the camp fire1. She was understandably horrified by this, even after someone explained that the puppy had not been murdered. It had been killed accidentally by one of the larger dogs, and the person who was responsible for it had decided that this was the most respectful way to deal with its death. She always seemed a little wary of us after that.

Working beets can be a positive experience in many ways. There is a real camaraderie and a kind of solidarity that can develop out of living and working and eating and sleeping collectively with a group of people under trying conditions. There are people who make a kind of circuit together throughout the year, piling beets in Minnesota, raking blueberries in Maine, canning fish in Alaska, and doing a variety of other things. It’s one way to make work, and life, a little less alienating and isolating.

It can also be terrible. The extreme drunkenness and perpetual drug abuse can get to be a bit much, and working eighty-four hours a week in the freezing cold while sleeping on a pile of straw in a barn for a month and a half without any running water or electricity will really put you in the mood to not take any shit from anyone.

The work is really easy. A well-trained orangutan could run a beet piler. You press the same buttons and pull the same levers over and over and over. It’s mostly just really loud and monotonous and cold.

It’s also fairly dangerous. You have to keep an eye on all the tweaked out truckers so they don’t run you over. You have to make sure not to fall into the machine. Somebody gets killed on a beet pile somewhere in Minnesota or North Dakota almost every year.

The inside of the factory is even crazier. There are unfathomable mazes of incomprehensible machines, catwalks and conveyor belts to nowhere, and ancient engines caked in a foot of beet pulp. There is the deafening racket of a thousand endlessly grinding gears, an entire floor of the factory that is always about a hundred and thirty degrees, and a place called The Pit where no supervisor will ever go. The whole place is completely inhuman. There is no shortage of opportunities to hide—or to get maimed or killed.

I work outside on the pilers unless the weather is bad, but sometimes I work inside the factory. Here’s a story. One day, I clock in and the bossman gives me a great big squeegee. He takes me to a particular pipe deep in the bowels of the factory which has sprung an enormous leak and is spraying massive amounts of half-processed syrup everywhere. “Mop up this juice,” he says, and then leaves, never to be seen again. So for twelve hours, the pipe runneth over, and I push the lake of juice—which never gets any smaller—down a drain. The drain feeds into a sump pump, which then pumps right back into the pipe!

Afterwards, while meditating on the absurdity of that task, I watched a couple of guys with a backhoe spend half the day digging a big hole in the ground, take lunch, and spend the rest of the day filling it back in. I started to imagine that everyone there was doing the same thing on some level. The welders cut slabs of steel in half, take lunch, and weld them back together; the mechanics disassemble engines, take lunch, and put them back together; and the whole place is actually a giant meth lab or loss leader for the Mafia. There’s the method to the madness of production for you.

The factory is supposed to be owned cooperatively by the farmers, but the evil agribusiness giant Cargill has its hands in the management of it. There was a month-long lockout last summer, when the union overwhelmingly rejected a contract that would have left workers with fewer benefits and higher health insurance costs. The lockout was wildly unpopular, and was eventually resolved, but the town and the factory are behind the times in a lot of ways. I have no doubt that the next few years will see more attempts to bust the union, and more of the downsizing, automation, and outsourcing that have already decimated most of the decent paying industrial jobs in the rest of the country. The beet plant will be an interesting arena of struggle when this does inevitably happen. There is certainly the possibility there for profound alliances to be born out of necessity amongst workers of diverse racial and cultural backgrounds.

The beet harvest works pretty well for me, and I keep going back, but I sure am glad to get the hell gone the minute I’m done. As soon as I get there, it feels like I never left, and it only ever takes about a week or so before I start having dreams about beets again. I can’t imagine how hard it must be to stomach working there every day for years on end. I do know that the company had to start making full-time workers clock in by scanning their retinas because so many people were scamming the timecards.

Last year, someone started writing “BDTF!” everywhere. Burn Down the Factory! Remember that song by Fifteen? It started turning up on the pilers, in the factory, in town, scrawled in the dust on the sides of cars in all manner of different handwriting styles. Maybe it was just the kids who were doing it, but maybe not.

Make no mistake about it: sugar is evil. It’s addictive, it rots your teeth, and it’s largely responsible for an epidemic of diabetes among poor people in this country. The process by which it is produced wastes a staggering amount of water, is horrifically destructive to the environment, and is viscerally just plain gross.

You can’t have your cake and eat it, too. If you want that sugar, you have to accept that huge amounts of land will be used to grow the beets, that enormous quantities of pesticides and fertilizers will be used on that land, that there will be a sacrifice zone somewhere on a totally denuded moonscape where the factory will go, that some folks will spend the best years of their lives inside that factory, and that a mountain of fossil fuels will be burned to power it. You also have to accept that some doped up crust punk is probably going to poop in the beet pile. In my opinion, it’s just not worth it.

When I first started working at the plant, I swore I would never eat anything with beet sugar in it again. Later, I started thinking about where cane sugar must come from, or corn syrup, or any kind of processed food, period. It all comes from some factory, somewhere. It’s sobering to realize that the whole way that food is produced and distributed in our civilization is so deranged and destructive. The problem is a whole lot bigger than almost anyone cares to admit.

There are a lot of good people—including myself—whose livelihoods are dependent on that factory, or on others like it, or on all sorts of other messed up jobs. I wholeheartedly support workers’ efforts to better their lot within the confines of industrial capitalism, but I’ll be honest—ultimately, I’d like to see the beet plant wiped off the face of the fucking earth. I want to give the land a chance to recover, and I want to be part of a society where that would be possible. I know that’s not going to happen without some truly revolutionary change.

Sometimes I will be sitting up in the booth running the piler, looking through the clouds of dust at the pillars of smoke and steam rising out of the factory, and it will hit me right in the chest: two hundred years ago, this was a tallgrass prairie teeming with buffalo, and now here I am like every other white person, trying to make a buck off of this land. I don’t exactly feel guilty about it; I am trapped in this heartless economy just like so many others, and I have to make some compromises if I am going to have any resources to fight it with. If I am going to make those kinds of compromises, though, I do feel a very grave responsibility to follow through on that commitment to fight. I’m willing to bet that I’m not the only one who feels that way.

Burn down the factory.

Dedicated to the memories of Oakle, Justin, Mosca, Jared, Steph, and Flee—fellow beet pilers who have passed away since this article was first published. You are missed, all of you.

-

Author’s note: Please let me take this opportunity to assure the gentle reader that I played no part in the puppy skinning. Thank you very much. ↩