As Election Day approaches in a context of anxiety about the prospect of Donald Trump attempting to hold onto power by force or cunning, the revolutionary potential that was palpable in early June has receded almost beyond the horizon. Anarchism, abolitionism, and direct action tactics have gained traction throughout the Trump era; thanks to the fearmongering of the administration, anarchists have as much visibility as we have experienced in a century. Yet once again, we are watching the election crowd out any other subject or strategy. Many anarchists, despite decades of rejecting representative democracy, are focused on hoping for a Biden victory—or trying to figure out how to block a Trump coup, lest democracy give way to autocracy. Others are echoing the far right in anticipating a civil war.

This is an old story, in which the twin threats of tyranny and civil war serve to discipline rebels back into supporting representative democracy, foreclosing the possibility of revolutionary change. But what if we want none of these—neither tyranny, nor civil war, nor to perpetually settle for being ruled by the lesser of two evils?

Subtle signs of unrest.

The best this system can offer us.

The Lesser of Two Evils

It’s not surprising that anarchists are concerned about the outcome of the election. Which administration comes to power—whether by electoral victory or by other means—will determine what kind of challenges we confront as we continue fighting to abolish police, prisons, borders, and other forms of oppression.

Here is the strongest argument we can imagine for voting: if we understand ourselves as engaged in an outright conflict with an opposing army comprised of all the forces of the state, it might make sense to take advantage of a chance, however small, to influence who will lead that army against us. From this perspective, it could be worth taking a half hour to cast a ballot—assuming there really is no more effective way to employ that particular half hour—but it could never justify diverting our attention from our offensive efforts or letting our enemies know where we sleep at night.1 (To those who worry that voting legitimizes our rulers, we might counter that the chief way we legitimize their rule is by not overthrowing them.)

Of course, the vast majority of people do not understand voting this way. The liberal obsession with voting as the be-all-end-all of political participation is a symptom of—and an alibi for—a perverse refusal to take responsibility for all the more effective ways that one can go about making change. Likewise, leftists who grant that the state presents a structural obstacle to their aspirations nonetheless tend to get their hopes up that the periodic reign of the lesser of two evils represents a step towards a better world rather than a way to stabilize the existing order. Consequently, they are always taken by surprise by the ways that state actors coopt and undermine their efforts.

Take the Workers Party in Brazil, Syriza in Greece, and—not so long ago—Barack Obama in the United States. All of these used progressive rhetoric and minor social reforms as cover to continue implementing a neoliberal agenda and cracking down on movements for social change, stoking popular disillusionment and ultimately creating the conditions for the far right to come to power. Only by comparison with Bolsonaro, New Democracy, and Trump—the far-right successors whose victories they rendered inevitable—can these administrations seem desirable to anyone on the left.

This time around, no one has any illusions that progress or reform are anywhere on the ballot. Cynicism abounds. If, in his first presidential campaign, Trump essentially promised that he would return the white working class to the 1950s, Joe Biden is proposing to take America back in time to 2016. Politically speaking, Biden is a nonentity representing voters’ fear of being ruled by Trump, their despair of ever seeing meaningful change through the political system, and their failure to imagine a more effective approach to self-determination.

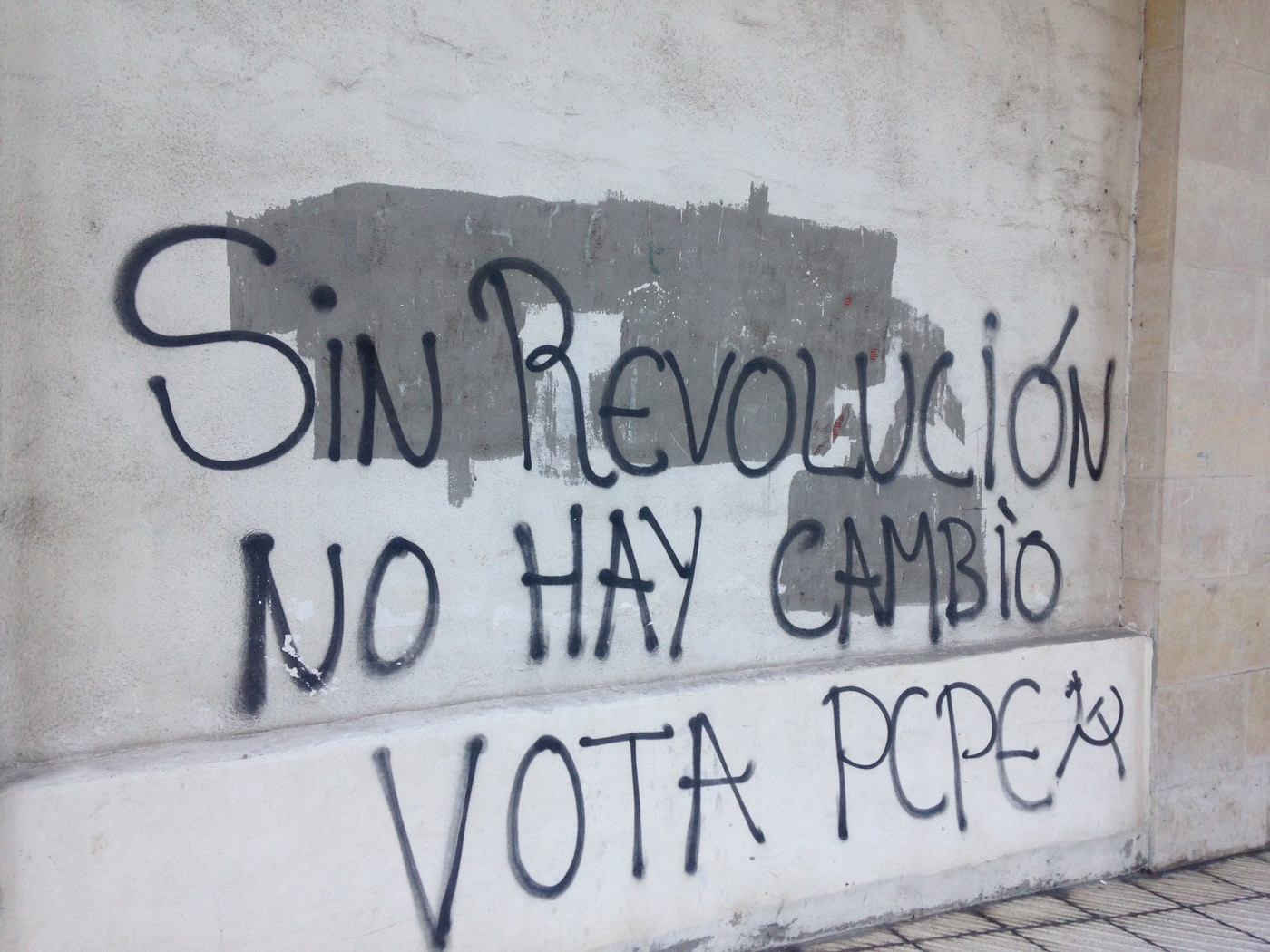

“Without revolution, there is no change. Vote PCPE!” This graffiti promoting the Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain aptly illustrates the contradictions of the leftist relationship to state democracy. Since the mid-19th century, Marx and his successors have acknowledged that there are structural reasons that the state does not serve the working class—while nonetheless urging workers to form parties and run for office.

All the Voting in the World

The more we focus on the election, the more we tend to internalize the logic of electoral politics: representation, majority rule, sovereignty as a winner-take-all competition, deference to procedure. Liberal concerns about preserving the rule of law and reforming the Electoral College serve to instill these premises.

For example—if the reason that it would be unconscionable to accept a second Trump term is that we believe that the majority of duly registered voters in this country oppose his candidacy, what if Trump surprises everyone again by winning the election with a solid majority of the electoral college, or even winning the popular vote? Will we then be duty-bound to accept his authority and obey the rulings of his Supreme Court?

From our standpoint, it is moral cowardice to frame the problem with Trump remaining in power as a concern that he might do so illegally. The people who are focusing on this are forgetting that the reason we’re in this mess in the first place is because Trump was already elected through the same democratic electoral system that they are urging us to defend at all costs. Focusing on the possibility that Trump might pull off an underhanded victory this time around is tantamount to priming everyone who opposes Trump to be prepared to give up fighting and accept another four years of his administration if he wins “fair and square.” Just as significantly, this serves to accustom the same people to complacency if Biden takes power but goes on enforcing at least some of the policies of the Trump era—as he undoubtedly will. Democracy itself is the problem, beguiling people to disregard their own consciences in favor of protocol, regardless of the cost in human suffering.

As anarchists, we didn’t set out to interrupt Trump’s inauguration because he lost the popular vote in 2016—we did it because we opposed his entire agenda and the idea that anyone should be able to wield that much power in the first place. We didn’t shut down airports because we anticipated that a duly appointed judge would eventually rule Trump’s Muslim ban unconstitutional—we did it because we believe that all human beings deserve the right to travel freely, whatever any president, judge, or voting bloc decrees. Our ethical compass is not majoritarian or procedural. Even if Trump were reelected with 100% of registered voters casting their ballots in his favor,2 we would continue to stand up to his attacks on immigrants, his federal interventions against Black Lives Matter protests, his force-propped authority.

There is nothing inherently just about the will of the majority, any more than there is anything inherently ethical or honorable about obeying the law. If you really want to do away with injustice, make it impossible for any group—be it a minority or a majority—to systematically dominate others. Until we build extensive horizontal networks of solidarity to accomplish this, tyrants like Trump will continue coming to power, and centrists like Joe Biden will continue trying to meet them halfway in a manner that ratchets our society ever closer to tyranny, and all the voting in the world won’t help.

“Everything that happened in Nazi Germany was legal. It happened in courtrooms, just like this. It was done by judges, judges who wore robes and judges who quoted the law and judges who said ‘This is the law, respect it.’”

-Jerry Rubin, February 15, 1970, facing sentencing for contempt of court.

How the Center Uses the Right

The threat presented by Trump’s candidacy and the violence of his supporters is convenient for centrists like Joe Biden and his supporters at the New York Times. They have already spent the summer using this excuse to urge protesters to exit the streets and give up their leverage on murderous police departments, baselessly suggesting that protests could drive voters into Trump’s arms.

In fact, if we study the polls over the course of 2020, Biden consolidated his lead after the George Floyd Rebellion got underway at the end of May; Trump only began to regain ground when the protests died down. If Trump loses this election and fails to retain power by other means, much of the credit must go to the rebels for compelling a subset of the ruling class to shift their allegiances to Biden by showing that four more years of Trump could render the United States ungovernable.

Centrists have always benefitted from the threat posed by the far right. Thanks to Trump, if Biden wins the election and secures power, millions of people who have every reason to fight against his express agenda will breathe a sigh of relief all the same. Liberals who would have continued to protest against racist immigration policies and police violence under Trump will quietly accept them under Biden, leaving the radicals who continue to oppose them isolated and exposed.

We’ve come a long way since June 2020—a long way the wrong way. In the immediate aftermath of the uprising, when people around the country had seen demonstrators in Minneapolis abolish a police precinct via direct action, it was finally possible to imagine doing away with the institution of policing itself. Reformists diluted this bold proposition, substituting their proposal to “defund” the police via lobbying. Unsurprisingly, moving the struggle back to the terrain of party politics and government procedure produced dismal results. Now that the contest between Biden and Trump occupies everyone’s attention, even defunding the police seems hopelessly idealistic.

So the Biden campaign represents the counterrevolution, no less than Donald Trump does. Trump’s absurd efforts to portray Biden as a far-left radical mobilize right-wing voters, but they also serve to close the Overton window to the left, framing the Biden campaign as the most radical platform conceivable.

This tendency to water down radical proposals and reduce the scope of the popular imagination is inherent in majoritarian democracy. The exigencies of competing to form the biggest voting bloc in order to capture power tend to reduce all political platforms to the lowest common denominator, suppressing difference. Minorities of all kinds are structurally compelled to become junior partners in coalitions that have little incentive to prioritize their needs. Centralization gives rise to homogenization, marginalizing those who will not or cannot pretend to be like everyone else, reinforcing the existing order as the only possible reality.

Pressuring people to support the lesser of two evils rather than pursuing their own dreams, electoral politics puts those dreams further and further out of reach.

Graffiti in Italy: “Death to democracy. Anarchy and freedom!”

Towards Civil War?

So what’s the alternative? If we don’t grant whichever politician wins the election the right to govern us, what does that mean for the future of the United States of America? If the consensus reality imposed by majoritarian democracy makes radical change impossible, how do we proceed?

The far right has already advanced their answer to these questions: civil war. If they cannot retain control of the state—the machinery of centralized violence—by electoral means, they are threatening to take violence into their own hands.

Some anti-fascists have adopted this rhetoric as well—and indeed, for some, the war has already arrived. “I see a civil war right around the corner,” Michael Reinoehl said to a reporter immediately before police murdered him in cold blood.

Most of those who warn of impending civil war aren’t explicitly advocating for it—they are just arguing that we should be prepared. Yet, as Emma Goldman spelled out in her essay “Preparedness, the Road to Universal Slaughter,” preparing for war can hasten its arrival. It can also make it difficult to recognize other possibilities.

The reasons that the far right are clamoring for civil war are complex. At the grassroots level, rank-and-file racists sense that they are on the losing end of the culture war and demographic shifts. Some have apparently concluded that the longer they put off open hostilities, the worse their position becomes. As they radicalize, demagogues like Donald Trump and Tucker Carlson must radicalize along with them in order to retain their loyalty.

Meanwhile, the extractive industries that supply much of the Republican Party’s funding are concerned about these demographic changes eroding their voter base, leading to increased taxation and environmental regulations. They likely see pandemic safety measures as a practice run for ecological measures that could cut into their profits permanently—COVID-19 denial and climate change denial arise from the same sectors. They intend to keep maximizing their profits at all costs, ecological catastrophe and civil strife notwithstanding. Just as the George Floyd rebellion exerted leverage on the institutions of our society, Republicans aim to use the threat of mass violence as leverage to preserve the status quo.

But do we stand to gain anything from escalating towards civil war? If the far right are calling for it, we should be especially suspicious of this paradigm.

September 5, 2020: Militia members in Louisville, Kentucky.

What Democracy and Civil War Have in Common

Democracy is often framed as the alternative to civil war. The idea is that we have democratic institutions so everyone won’t just kill each other in direct pursuit of power. This is the social contract that liberals accuse Trump of violating.

But if, as Carl von Clausewitz said, war is simply politics by other means, we should consider what representative democracy and civil war have in common. Both are essentially winner-takes-all struggles in which adversaries compete to control the state—i.e., to achieve a monopoly on violence, control, and perceived legitimacy. The exigencies of civil war, no less than the exigencies of electoral competition, reward those who can appeal to the wealthy and powerful for resources and those who can reduce their agenda to the lowest common denominator in order to build mass.3

“Guided by the experiences of those who participated in the original uprising in Syria, we can learn a lot about the hazards of militarism in revolutionary struggle. Once the conflict with Assad’s government shifted from strikes and subversion to militarized violence, those who were backed by state or institutional actors were able to centralize themselves as the protagonists; power collected in the hands of Islamists and other reactionaries. As Italian insurrectionist anarchists famously argued, ‘the force of insurrection is social, not military.’ The uprising didn’t spread far enough fast enough to become a revolution. Instead, it turned into a gruesome civil war, bringing the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ to a close and with it the worldwide wave of revolts.”

If war is politics by other means, then politics as we know it—the state and its most resilient and stable form to date, representative democracy—may have emerged as war by other means. Militarized conflicts that compel everyone to take sides according to a binary framework tend to engender the same hierarchies, the same mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion, and the same centralization of coercive force that are fundamental to the state. The state emerges when one side wins a war and imposes its authority; civil war resumes when the incentives to compete for power via elections rather than brute force break down. But in the end, civil war per se is bound to end with the reemergence of the state; anything else would require a revolution that transforms the participants, not a binary conflict that ends with one party dominating the other. In this regard, if war is the health of the state, as Randolph Bourne wrote, we might say that goes for civil war as well.

A brief review of US history confirms that representative democracy has always existed on a spectrum with civil war. Bleeding Kansas is perhaps the best known example of this: for years, people fought and killed each other in a struggle to determine whether Kansas would vote to preserve the institution of slavery. The same rivals who would beat and shoot each other one week would cast ballots against each other the next, then go back to beating and shooting each other.

Trump and his supporters are part of a centuries-old tradition that understands democracy as a variant of civil war. Trump’s strategy of voter intimidation, for example, draws on a long heritage extending back to the Plug Uglies and other gangs that employed violence to systematically rig the outcome of elections.

“Stealing elections is how democracy works. It’s how it has always worked. If you legitimize a monopoly on coercive force and authority by claiming to represent the will of the people, then obviously subsequent power struggles will focus on defining which people constitute ‘the People.’”

-Peter Gelderloos, “Preparing for Electoral Unrest and a Right-Wing Power Grab”

In this context, we can recognize Trump’s emphasis on Nuremberg-style mass rallies as a demagogic form of democracy originally descended from open clashes within the polity:

“Winning an election is one way to claim the legitimacy of having been chosen by the people; being acclaimed in the streets or instituted by popular violence are other ways. In ancient Sparta, leaders were elected to the council of elders by a shouting contest—the candidate who received the loudest applause won. The technical term for this is acclamation… This is the oldest form of democracy—Spartan rather than Athenian—in which the masses legitimize a movement or ruling party as representative by acclaiming it in person, rather than through elections.

So civil war is not a solution to the problems with representative democracy. It simply continues the logic of the majoritarian contest for power on another terrain, the terrain of open violence.

Both representative democracy and civil war are essentially spectator sports, subordinating the agency of ordinary people to politicians or militia members.

If the risk of focusing on the election alongside liberals is that we will internalize the logic of electoral politics, then one risk of spending so much time fighting the far right is that we will internalize their premises, as well, coming to assume that the only alternative to electoral politics is militarized clashes. The proliferation of guns at demonstrations seems to reflect this—not so much the guns themselves as the way that they are coming to dominate our imaginations.

A few accelerationists have welcomed the escalation of hostilities, hailing a post-democratic era in which those who are mobilized by different ideologies, value systems, and notions of belonging will fight it out openly. This is redundant at best: we already live in an era of civil war that will almost certainly intensify. Ukraine—Charlottesville—one, two, many Syrias. The question is not how to foment social conflict, but how to maximize the likelihood that the outcome of these conflicts will be more freedom, more egalitarian relations, and hopefully, in the long run, more harmony.

Ordinarily, the anarchist position on elections is to reject the centrality of voting as the be-all-end-all of political participation. In 2020, it is just as important to reject civil war as the alternative. This is not an argument against partisanship per se—rather, it’s a question of what kind of partisanship we want to foster. Rather than joining one of the rival factions competing for control of the state, let’s look for ways to transform these struggles and the social bodies that are engaged in them, ways to broaden the horizons of possibility.

Instead of Civil War—Contagious Refusal and Revolt

In place of civil war, which pits discrete factions against each other in a contest of arms, we aim to spread revolt on a horizontal and decentralized basis, destabilizing the institutions of power and the allegiances and conflicts that underpin them. The first step in this process is to dismiss the idea that any law, majority, or leadership has an inherent claim on our obedience. The second step is to throw out any lingering romanticism about what we can accomplish by force of arms alone—we seek to transform our relations with others, not to exterminate them. The third step is to refuse our roles in perpetuating the existing order, whether as active participants in it or passive accomplices who permit it to continue, setting contagious examples of rebellion that can spread throughout society at large.

The ungovernable uprisings of May and June demonstrated how effective this can be. Civil war revolves around fighting an enemy; in revolt, we offer those who are not yet involved roles as protagonists in their own version of a shared narrative. The further rebellion and refusal spread from one sector of society to the next, the greater the potential for real social change. Altering the conditions in which people conceptualize the issues that affect them and decide how to align themselves, we can redraw the lines of conflict—for example, from “conservatives versus liberals” to “residents versus evictions.”

We should also explore all the other ways we can relate to each other besides warfare, setting positive precedents for coexisting and cooperating across lines of difference. The mutual aid programs that have multiplied since March have the virtue of creating connections between people who might not otherwise identify with each other, diminishing the likelihood that conflicts will escalate to lethal force. In addition to interrupting the prevailing order, we also have to weave a new social fabric, making peace as an offensive measure against needless destructive conflicts.4

Necessary but not sufficient.

This November, if Trump attempts to hold on to power and legalistic solutions fail to resolve the crisis, some liberal centrists will press us to serve as the shock troops of democracy, taking risks that they would never take themselves in order to preserve the integrity of an electoral system that has always suppressed our voices and our autonomy. Far-right Republicans and outright fascists would love to see us locked in symmetrical warfare with better-armed militias who want nothing more than a fixed target and a legitimate excuse to employ their weapons. We should be careful not to end up playing either of these roles, but to chart our own path, evaluating the effectiveness of our actions according to the extent to which they achieve our goals.

If armed militias attempt to seize the capitol buildings to pressure the state to permit Trump to retain office, reprising the tactic they tested out during the “re-open” protests in April, we should not go to meet them there in open combat. Rather, we should identify all the pressure points throughout this society via which we can exert leverage asymmetrically, all the supply chains that deliver the resources that the militias, their backers, and the state itself depend on. Imagine a wave of blockades, strikes, self-organized assemblies, and cooperative actions targeting a variety of aspects of the state and the economy, arising from a multiplicity of overlapping forms of organization that cannot all be coopted by Democrats eager to dictate terms, setting precedents that will stand long after this particular political moment has passed. By seizing the opportunity to interpose our own narratives and our own agendas, speaking directly to the everyday needs of ordinary people, we could come out of the crisis stronger and better connected.

If there has to be a crisis, let’s make the most of it.

The Good News Is—We’re on Our Own

If there is any unambiguously good news this electoral season, it is that neither of the major candidates represent anything like a radical agenda. Had Bernie Sanders become the Democratic candidate and won the election, he would have faced the same internal sabotage from career politicians that prevented him from winning the nomination, not to mention the structural challenges that doomed the socialist aspirations of the Workers Party and Syriza. His efforts to temper cutthroat capitalism could only have failed, inducing some of his supporters to embrace centrist realpolitik while leaving others disillusioned and bitter. Better that the center is discredited under Biden.

2016 was a lifetime ago.

For years, we have argued that owing to the consequences of neoliberal globalization, the state can do little to mitigate the impact of capitalism on the general public. Under these conditions, no party can hold power long without losing legitimacy and catalyzing opposition. We saw this under the Workers Party in Brazil, under Syriza in Greece, under Obama in the US. Now we have seen it under Trump as well—the grassroots nationalists and white supremacists who suffered so many reverses under his administration would probably be in a stronger position today if they had been able to present themselves as the opposition to an unpopular Clinton administration. As we argued the day after Trump won the 2016 election:

Let us look for silver linings in this cloud of oncoming tear gas. Perhaps it is for the best that someone like Trump is coming to power now, rather than four years hence. Let the right wing demonstrate that their solutions are just as inadequate as those proposed from the Left. In a time of economic crises, ecological collapse, and spreading war, the state is a hot potato: no one will be able to hold it long.

If it is true that state power has become a hot potato that burns whoever tries to hold it—a thesis that will be tested again this November—the last thing we need is for our revolutionary proposals to be conflated with the watered-down program of some political party. If we are to make deep and lasting change, our movements must continue growing from the grassroots, demonstrating the efficacy of direct action, fostering an appetite for fundamental change, never confused with a party program that could be implemented through the existing apparatus of state power.

If Biden succeeds in securing the presidency, we must immediately pivot to confronting him, showing all the ways that his administration will continue carrying out Trump’s agenda. There must be no confusion about the distance between grassroots social movements and the political party in the White House.

Under a Biden presidency, we will likely see increasing attacks from a frustrated far right. The millions of racists Trump has emboldened will not simply shift their allegiances to the likes of the Lincoln Project if he is defeated at the polls. We should be able to weather their attacks the same way we defeated the fighting formations of the far right during the Trump era, provided our comrades on the left and towards the center do not leave us to fight alone. Once more, this will be determined by whether we permit Biden and his cronies to create the impression that the crisis of the Trump years has been resolved.

In any case, rather than facing a choice between democracy and civil war, we face a future that almost certainly holds both. It’s up to us to make sure that it holds something else as well—contagious momentum towards liberation.

As we wrote four years ago, hours after Trump won the election,

Cradle the seed, even in the volcano’s mouth.

-

In many states, registering to vote renders your home address a matter of public record. Those who wish to avoid this can register as homeless. ↩

-

Incidentally, no US presidential candidate has ever received the votes of even a quarter of the population. ↩

-

In an interview earlier this month, a longtime anarchist fighter in Rojava described how this played out in the early years of the Syrian Civil War: “As the fights escalated and the war intensified, weaker factions were absorbed by stronger factions or just disbanded. When ISIS started to penetrate into Syria in 2013, the opposition factions had to chose sides—with Daesh or against them.” ↩

-

In this regard, we are inspired by the recent anti-war statements from rebels on both sides of the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia. We can learn a lot from anarchists and other anti-militarists who lived through the civil wars in former Yugoslavia, Colombia, Peru, and Northern Ireland. ↩