On November 30 and December 1, the 2018 G20 summit will bring together the rulers of the 20 most powerful nations for a meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In the third installment of our coverage of the 2018 G20 summit, our international correspondents describe the unprecedentedly massive security operation that is accompanying this summit, the international protest mobilization, and police violence against the poor population in the periphery.

Tuesday, November 20

Border Controls, Security Zones, and a City Blockade

The government announced on Monday, November 19 that it will be tightening border controls, focusing on the border triangle with Uruguay and Brazil as well as the international airport. They claimed to have “extensive international lists” and that they “will strictly prevent the entry of radical G20 protesters.” In case friends and activists are detained at the airport, the Protest Alliance has set up a round-the-clock legal emergency service.

On Tuesday, the “security junta” chaired by Minister Patricia Bullrich held a press conference; Bullrich is a machine of repression with an oligarchic family background and also some (decidedly dubious) past association with the Montoneros. Everyone expected large security zones and restrictions on freedom of movement, but the scope of what Bullrich announced went beyond the expectations of the assembled capitalist press.

The graded security zones will cover an area of about 20 square kilometers only in the inner-city area—a tenth of the total area of the capital. There will also be “variable corridors” and closed roads to the international airport 40 km away. Within the dark red security zone, the “Villa 31” is located—the so-called “Villa Miseria”—with its approximately 30,000 residents, which is close to the conference venue. As it appears, the residents are to be locked in or out of their homes and their neighborhood. They have virtually no lobby at all to advocate for them; on the contrary, they are highly stigmatized.

The square-shaped area below (to the south) in the following city plans is justified as “protection of the Theatro Colon”—where this Friday, the feudal dinner of the heads of state is to take place. However, the theater is not located in the middle of this zone, but close to the upper left edge, between the metro line B and the zone border. More than 200,000 inner city residents live in this square, which also houses the political and historical center of the city and the entire country, including the Congress and the Plaza de Mayo. The security zones also include the entire port, the inner-city airport, the city’s main arterial roads including the sixteen-lane Avenida of July 9, Retiro Central Station, large parts of the historic Recoleta district, and the expensive new Puerto Madero port quarter. For the latter two, we are talking about approximately 50,000 more residents who will be directly affected by the security around the summit. In addition, there is a smaller control area to the south, near the Plaza Constitución, which can only be explained by a “troop site” planned there.

In addition to all these security zones, restrictions on local public transport have been announced, on a scale that has never been implemented before at any previous summit. The entire regional rail network and the metro (“Subte”) network will be completely shut down during the G20. This will render travel impossible throughout the city. The same is true for all shipping traffic on the Rio de la Plata, the river that separates the neighboring cities of the metropolitan region and Montevideo in Uruguay from Buenos Aires.

On the other hand, some buses within Buenos Aires “may still run.”

All this is hard to swallow for city residents who have only experienced such conditions during general strikes. This time, however, the aim of the intervention is not a social concern—and certainly not “guaranteeing the safety of the summit”—but rather, cutting off or inhibiting the flow of protest towards the center. In the city center, only police and politicians should move freely. Everyone else—the inconvenient others—should leave for the countryside or stay locked inside their homes.

The affected areas.

The affected areas.

Wednesday, November 21

A Book, an Article, and a Call for a Demonstration

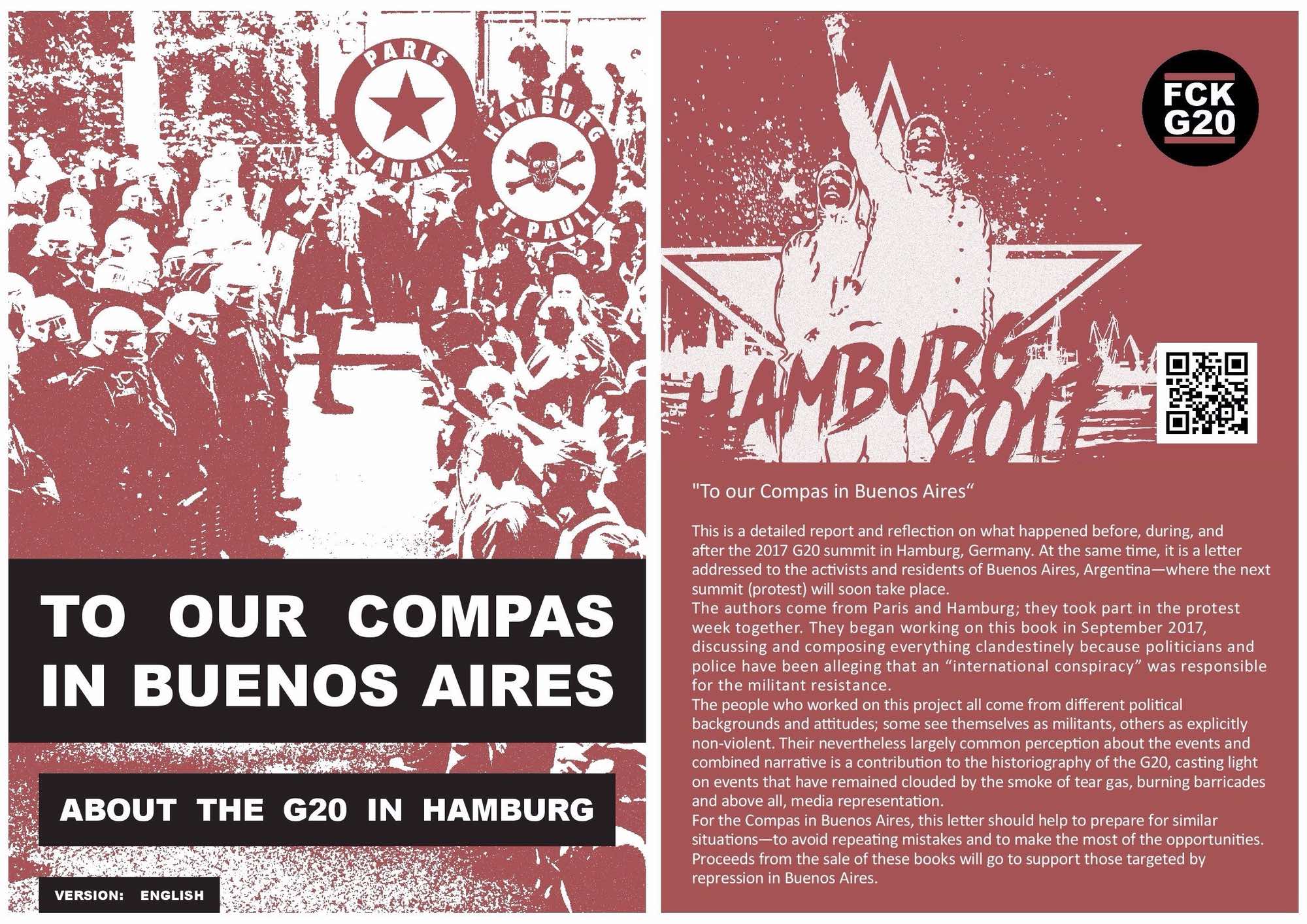

On Wednesday, the widely read national online newspaper Infobae published an article about the multilingual book To Our Compas in Buenos Aires by activists from Hamburg and Paris. Infobae is considered to be close to the reigning government; it is often cited by the German Foreign Office as a “serious source.” The lengthy article was titled “Take Care Compas—The Handbook of International Protest that the Government Is Studying ahead of the G20.”

First, the text briefly presents the concerns of the Argentine government, highlighting the alleged threat posed by international opponents of globalization. After that, however, the article quotes the book at great length in a fairly unbiased manner. For example, the book description appears unabridged and passages referring to the forthcoming summit in Buenos Aires are highlighted. The text is framed as a kind of “guide to protest,” though this is already refuted by the quotations. However, the article sketches a relatively comprehensive picture of the courses of events in Hamburg, chiefly through the quotations. Infobae describes it as “ridiculous” that the authors of the book describe the attendance of 80,000 people at the central demonstration as a “success”—a rather small number of participants, by Buenos Aires standards.

Surprisingly, on the same day, the short call for a demonstration in Hamburg to show solidarity with the protests in Buenos Aires, translated into Spanish, appeared on the front of the local protest website in Buenos Aires. The call is for a demonstration on the afternoon of December 1 after an FC St. Pauli home game. The preceding evening, there will be a meeting in a left cultural center in Hamburg to follow the events in Buenos Aires. The December 1 demonstration is also intended as a reaction to the anticipated repression.

And International Protests?

In addition to those in Hamburg, parallel protests will take place in Paris and London. There are probably also plans elsewhere. Very few activists from Europe or North America will come to Buenos Aires, and not only because of the announced border controls. The flights are expensive and harmful to the environment, police repression is expected to be intense, and the strange conditions in which the G20 will take place in Argentina are likely to deter many more protesters.

The alliance “Confluencia” expects activists from neighboring countries. In view of limited resources and the long distances, however, even within South America, travelling to protests in neighboring countries is by no means standard. Now, the Argentine government has added the offensively announced border closure. The national government and international security management are doing everything they can to minimize the number of participants from outside Argentina. Even journeys from other regions of Argentina will be rendered considerably more difficult by the interruption of the railway connections into Buenos Aires. It is even conceivable that this will extend to regional train connections and bus routes. The announced repression is also having an effect: one of the larger Peronist trade unions has already toned down its mobilization for this reason and in view of next year’s elections. One does not want to be associated too much with the foreseeable (or even conjured up) “riots.”

Thursday, November 22

“No Roof, No Land, No Life”

This is the headline of the progressive, left-leaning daily newspaper Página 12. Rodolfo Orellana, 36 years old, of Bolivian origin and father of five children, is dead, most likely murdered by the police. What happened? In the early morning, between 100 and 200 residents attempted to occupy a vacant site in the huge suburb of Matanza. In fact, the owner had already signed a far-reaching temporary use agreement with the local neighborhood association, in which Rodolfo Orellana was also active. This agreement document has been pushed from office to office for a long time in order to take effect legally.

Despite this legal grey zone, the police immediately arrived at the occupation in full gear and shot numerous rubber bullets, seriously injuring several people. A video shows Rodolfo Orellana, likely after his death. As became known later during the autopsy, he died as a consequence of live ammunition entering his shoulder. Based on the exit wound, the shot must have hit him when he was in a stooped posture, either standing or squatting with his back to the murderer.

Police maintain that neither the bullet nor the shell were found; the caliber of the bullet is supposed to be determined in a second autopsy. The police deny the use of firearms, alleging that there were hostilities between Bolivian and Paraguayan groups within the occupiers. Since the bloody political unrest of 2002, it is forbidden for the police in Argentina to carry firearms during demonstrations—and even more so to use them. But it is absurd to imagine that now, during a brutal evacuation, the demonstrators would have shot each other under the eyes of the police.

There were four more arrests, including a mother who was “allowed” to have her baby in the police cell for a short time every three hours to breastfeed. On the following day, there was a fierce and emotionally moving protest rally in the city center.

Housing Shortage in the Periphery

Officially, the city of Buenos Aires covers only 203 km² with 2.9 million inhabitants; by contrast, Berlin covers 891 km² with 3.6 million. However, there are officially almost 14 million inhabitants in the immediate metropolitan area. In the periphery there are also some isolated “islands for the rich” and areas with a mixed character, but by and large, the “outskirts” range from poor to extremely poor districts and informal settlements. The social and cultural contrast to the official “capital” is dramatic.

The “suburb” Matanza (in English, “slaughter” or “bloodbath”) hosts 1.8 million inhabitants—as many as the city of Hamburg. There are also several “villas,” places with improvised buildings. The housing shortage is most clearly visible in these shantytowns and their surroundings. Migrants from neighboring countries often live in highly crowded and inhumane conditions. Empty spaces are often squatted in order to open up a little more space for survival and life. In addition, there is a widespread “economía popular” via which people organize their everyday lives. Rodolfo Orellana was an activist there.

Rodolfo Orellana, murdered by the police.

Income throughout Buenoes Aires

The proportion of “villas” as a form of housing in 2010.